Welcome to part five of our course! Below, you’ll find the contents of the video above in text form. We’re releasing the course one lesson a week over twelve weeks. Enjoy!

Now we’ll embark on a journey through history, experiencing the origins and progression of money. To evaluate each good used as money, we’ll learn about seven desirable properties in money.

How money starts

First, a bit about how money “starts up” in a community. First, communities bartered. Direct exchange, say strawberries for cows. Then at some point they started using primitive money, like shells. How did this happen?

Carl Menger, founder of the Austrian school, argued that money arose from individuals choosing what they thought was the best money for life or business. Eventually, the market converged on preferred money. People inventively and organically found the best good at being a store of value, medium of exchange, and unit of account over time. Bishop Oresme sings the same tune in his treatise on money.1

Desirable properties in money

Communities throughout history have found the following seven properties desirable in a good used as money:

Durable: The good must not be perishable or easily destroyed. This ensures that money can circulate in the economy in an acceptable and recognizable state. Thus wheat is not ideal. Gold, however, can withstand wear and tear.

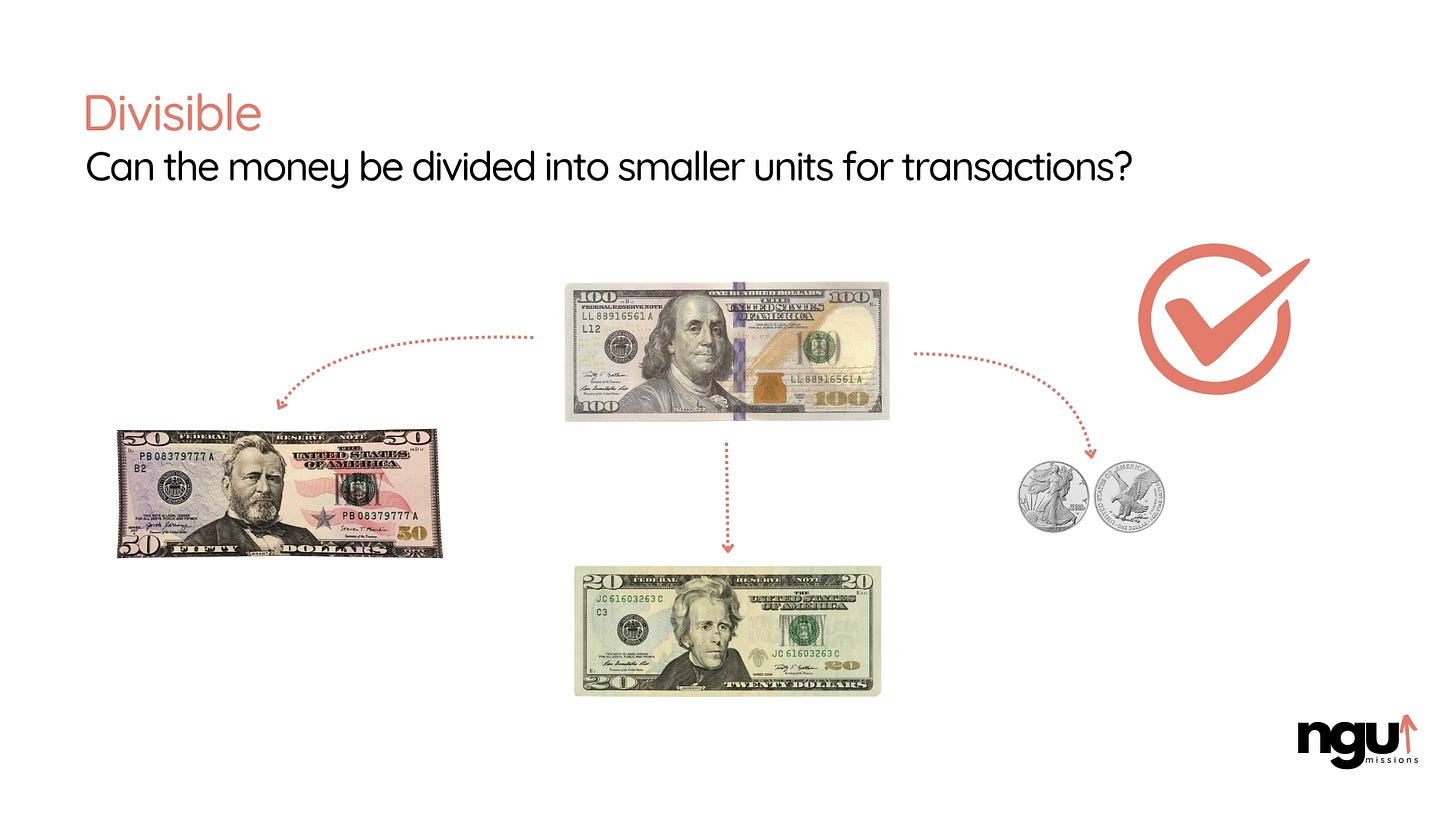

Divisible: The good must be easy to subdivide, for smaller and more precise transactions. Paper bills and coins can be easily divided.

Portable: The good must be easy to transport and store, allowing it to facilitate trade over long distances and making it possible to secure against loss or theft. A cow is thus less ideal than a gold bracelet.

Established history: The longer the good is perceived to have been valuable, the greater its appeal. The US dollar today has a long established history relative to bitcoin.

Scarce: “Scarce” means a limited availability of something. Perhaps most important for money to function as a store of value, scarcity taps into humans naturally valuing that which is rare—think of the one-of-a-kind Mona Lisa. However, we don’t want it too scarce; we can’t use the Mona Lisa as money. Instead, we want a balanced scarcity. As American legal scholar and cryptographer Nick Szabo termed it, money should have unforgeable costliness: the good must not be abundant or easy to obtain or produce in quantity, nor should it be too scarce or hard to obtain or produce at all.

Fungible: One specimen of the good should be interchangeable with another of equal quantity. Metal coins (standardized) are better than diamonds (irregular in shape and quality).

Verifiable: The good must be easy to quickly verify as authentic. Think of a store owner inspecting bills under light. Modern bills have improved anti-counterfeiting technology, like watermarks or holograms.

Now that we have our good money lens, now let's go on our historical money journey.

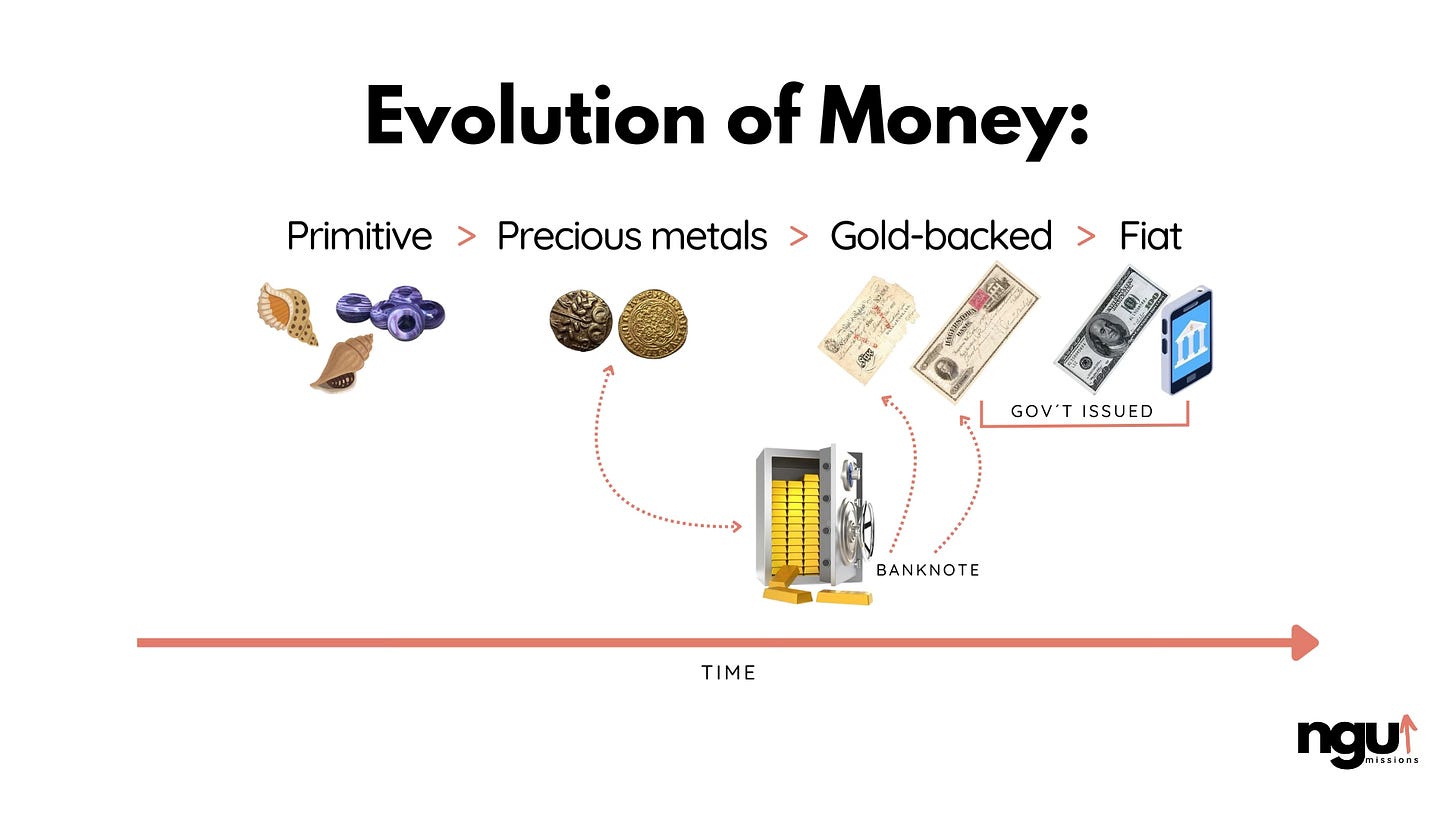

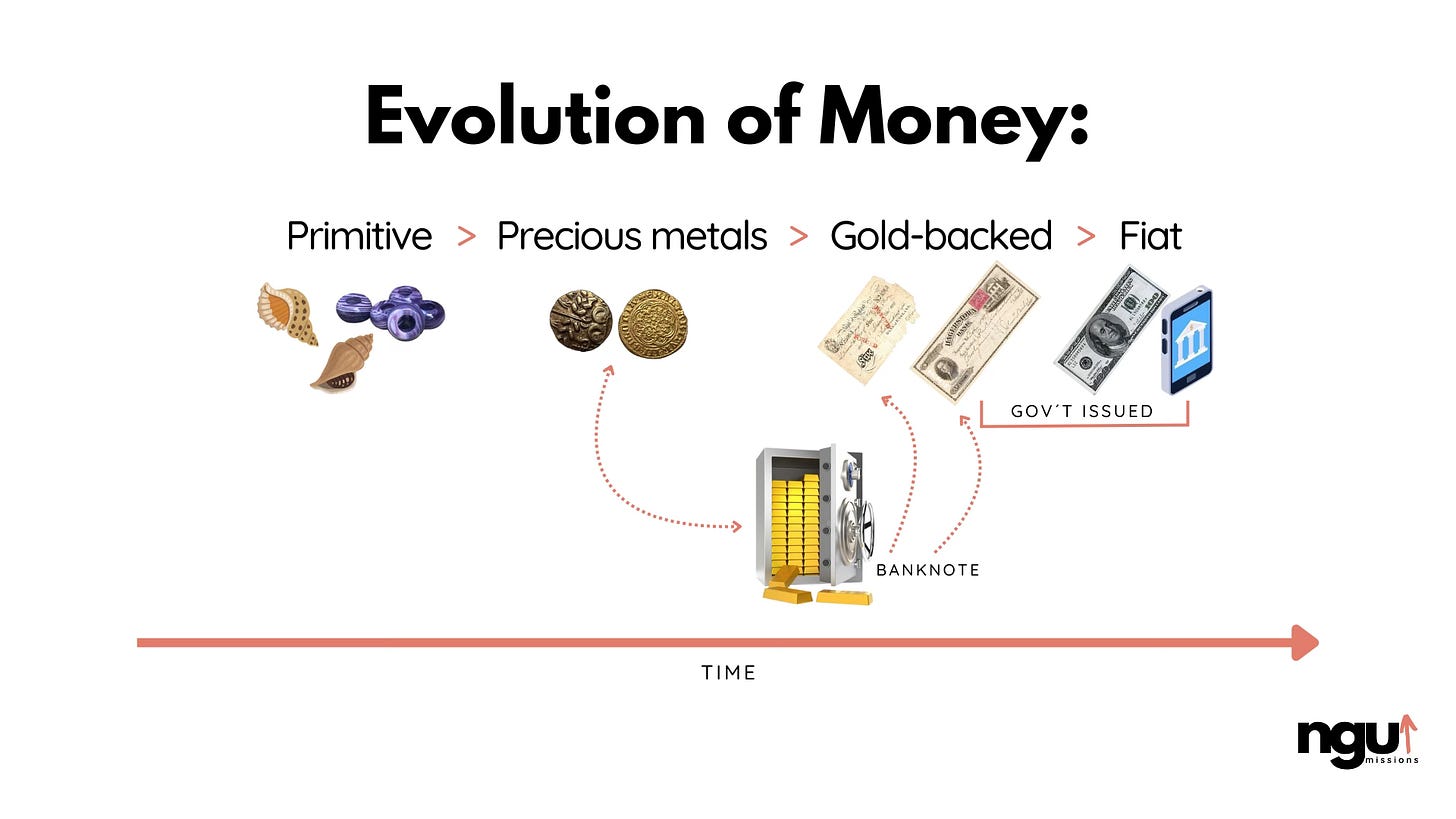

The evolution of money

Primitive money

We will begin with primitive forms of money, such as shells and beads crafted from local materials like stones, wood, and bone. These were used by societies worldwide.

But locally-sourced money had issues. For example, shells aren’t super durable, precise divisibility is difficult, and scarcity fluctuated as folks found or imported shells.

Precious metals

Humanity moved onward: metal money, primarily gold and silver, and sometimes other or mixed metals. Bishop Oresme preferred high-purity gold coins with a consistent weight and size, with a stamp from the coin issuer for verification.2

Metal coins were more durable and divisible. And portable, because you can condense value into a single coin and carry that instead of a great bunch of less valuable shells and beads.

However, the coins were heavy for large transactions, and some people abused the system by creating new fraudulent coins diluted with cheaper metals, which harms scarcity. The guilty included the Prince trying to finance expenditures or wars, hence Oresme’s treatise.

Gold-backed paper

Communities later moved on to paper receipts saying “we have this precious metal stored for you somewhere” as a form of money, and receipt holders could demand the actual metal at any time.

These paper receipts improved portability once again. No longer did you carry metal; large transactions were simple. The previous scarcity issue was shifted to the banks, who acted as trusted central issuers and custodians.

However, people began to notice suspicious activity within the banks; they were issuing more paper receipts than they had gold in storage, effectively creating money without sufficient asset backing. This practice led to bank runs and recessions.

Fiat money

Partly fiat, 1944-1971

The move to the next system was less about improving money, and more about attending to a crisis. By 1944, the difference between gold in each country’s banks and paper money created became so stark that a global financial crisis was imminent. So in July 1944, 730 delegates representing 44 nations met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire and agreed on a system:

The US dollar was tied to gold at $35 an ounce for government trades.

The IMF was created to manage other countries’ exchange rates with the dollar, which became the world’s main currency.

This led to more people using the US dollar.

The term “fiat money” comes from the Latin word “fiat,” which means “let it be done.” Here it means that this money’s value is established by government decree. During wartime instability, this agreement temporarily stabilized the system, as it inspired confidence through international cooperation and clear exchange rate rules.

Fully fiat, 1971-today

But the stability didn’t last long. The US, in coordination with the other nations, continued to create more dollars than there was gold, and in 1971 President Nixon had to say no more gold at all. Since then, currencies have lacked direct asset backing, and now fluctuate based on market forces and government policies. Notably, a country’s central bank can now create money without accountability to an amount of stored value, like they had to with gold before.

Other fiat money changes

There have been other changes within the fiat money paradigm. In the 1950s, credit cards started to become popular. People started to use fiat money via plastic cards that allowed you to buy now and “settle your tab” later. Then with widespread internet adoption in the 2000s, people started to use fiat money online.

The main problem with fiat currencies is their lack of scarcity—nations have shown a persistent habit of “printing money” to solve short-term political problems.

Bills and coins…

Practically, we have used paper or plastic bills and metal coins for a long time, but, as you’ve seen, the value those things have represented have changed.

A reminder, our end goal is a stable money, and consistent money printing prevents that. In the next post, we’ll learn about the material and moral consequences of unstable fiat money you've likely felt.

Have feedback to improve this part of the course? Submit it anonymously here.

We’re taking next week off, so the next part of the course will be released on April 26.

Wishing you a blessed Holy Week!

Oresme, Nicole. Treatise on the Origin of Money, Part I (c. 1355).

Oresme, Nicole. Treatise on the Origin of Money, Part IV (c. 1355).

Share this post