Welcome to part four of our course! Below, you’ll find the contents of the video above in text form. We’re releasing the course one lesson a week over twelve weeks, and last week we were on mission in NYC, so this week you’ll get two. Enjoy!

In this post, we’ll learn about the three functions of money: store of value, medium of exchange, and unit of account, and how new forms of money—like Bitcoin—demonstrate these functions in stages.

In the last post, we learned that most people know money as a medium of exchange—that is, money facilitates trade. But it’s more than that, and the other two functions will help you understand how money today is broken.

Store of value

First, there’s money as a store of value. For example, you earn wages with your labor, then you put that money aside in your “nest egg”—money specifically put aside for future use, like retirement or emergencies. People here are using money as a tool to store value over time.

This is the first stage. Throughout history, goods like shells, beads, and gold initially gained demand as collectibles due to their unique properties or aesthetic appeal. Communities often first valued items like shells, beads, and gold for their inherent qualities—the beauty and portability of shells and beads, the luster and purity of gold, perhaps. Bitcoin was there as well in the early 2010s as a novel digital toy for internet enthusiasts. As more people recognize these inherent properties as interesting and also as suitable for storing value, demand grows, and the good begins to function as a “store of value.” People recognize that it is holding value over time, leading to more and more demand, as education and acceptance spread throughout society. This process causes the price of the good to increase, sometimes in a volatile way.

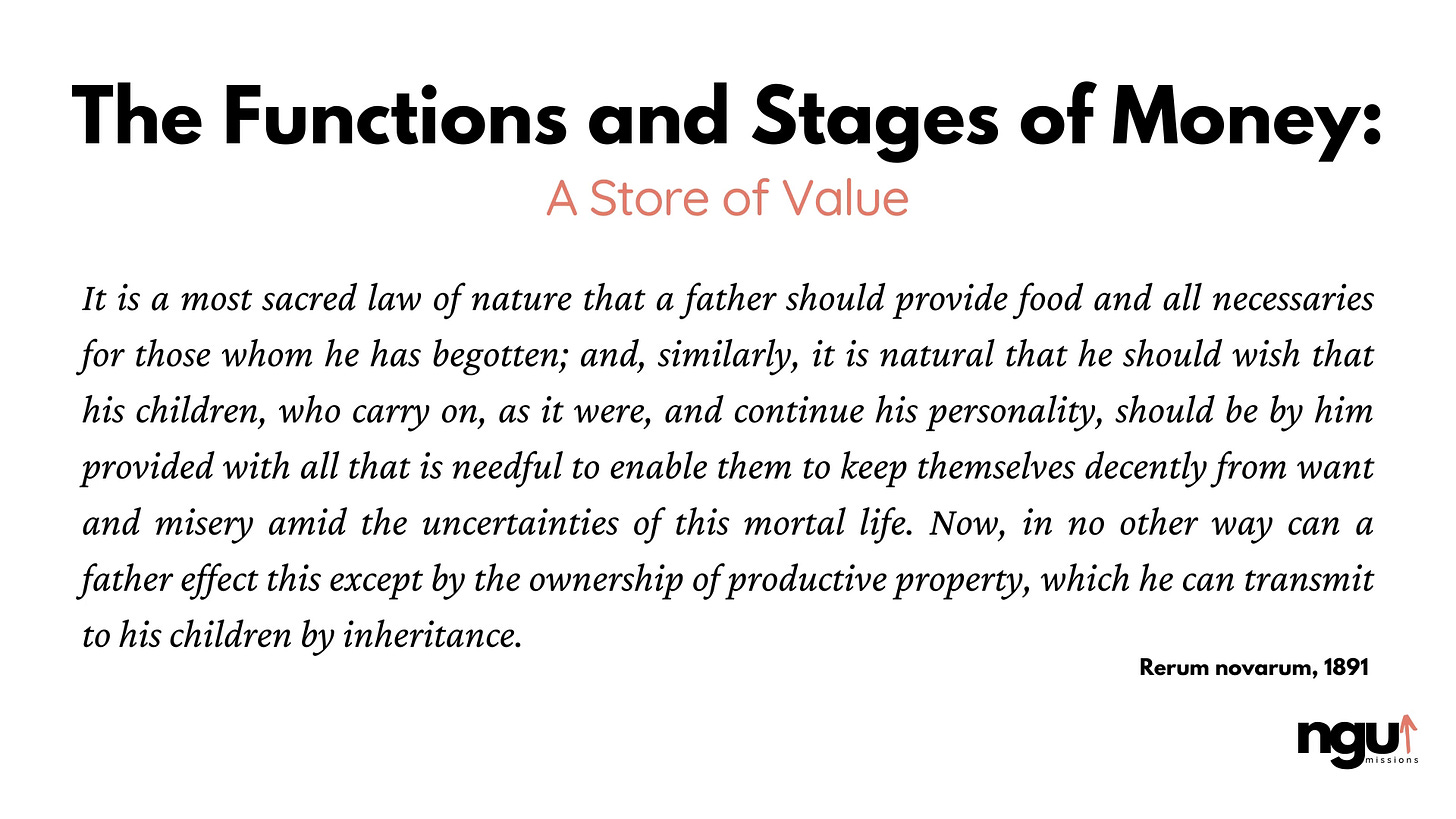

From a Catholic perspective, we must grasp “productive property” before we understand how Pope Leo XIII wants us to have a store of value. Pause and read his quote below.

“It is a most sacred law of nature that a father should provide food and all necessaries for those whom he has begotten; and, similarly, it is natural that he should wish that his children, who carry on, as it were, and continue his personality, should be by him provided with all that is needful to enable them to keep themselves decently from want and misery amid the uncertainties of this mortal life. Now, in no other way can a father effect this except by the ownership of productive property, which he can transmit to his children by inheritance.” —Pope Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, 1891 AD

In Catholic Social Teaching, productive property refers to assets, primarily land and tools, that enable families to earn livelihoods. Think of a tractor or a laptop. His Holiness emphasized productive property because it was tied to his vision of families having the means for self-sufficiency and flourishing.

Now money, like golds, shells, or beads, isn’t productive property. However, money as a store of value leads folks to invest in productive property. Just like last lesson, we’re going one layer below Rerum Novarum.

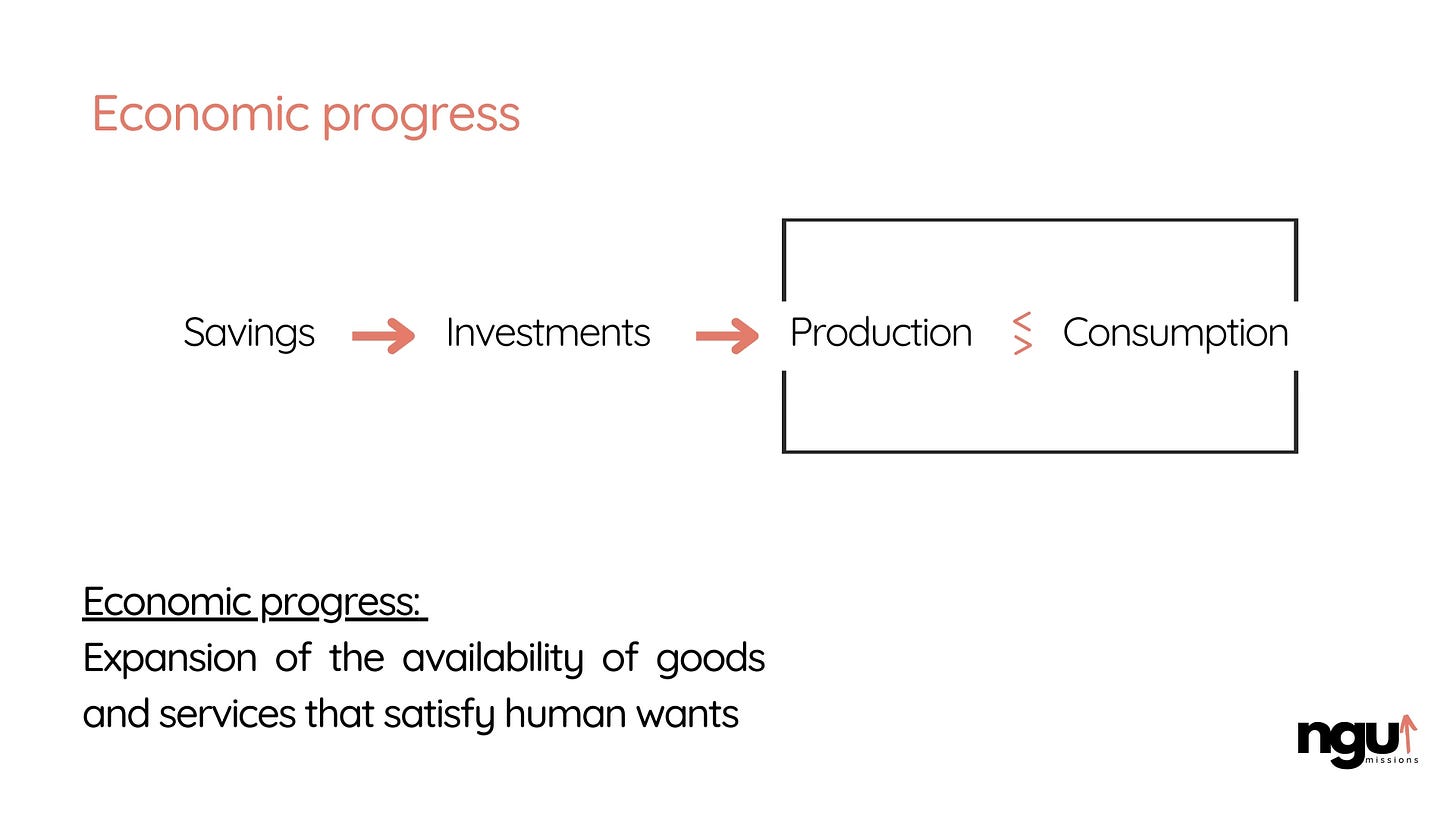

Here’s how it works. The Austrian school of economics framework has saving and investment as the engines of economic progress.

Saving is the initial act of forgoing present consumption, of whatever resources you possess.

Investment is the use of those saved resources to acquire productive property, like tools or land.

Saving therefore is the essential source of investment. Without saving, there is no investment in productive property. Then we use that productive property in a circular, interactive flow of producing goods and services and “consuming” them.

So production is the use of that productive property to create more goods and services. And consumption is the ultimate goal, made possible by increased production. Consumers consuming informs producers what to produce, creating a feedback loop.

The Austrian school calls this process economic progress. They define it as an expansion of the availability of goods and services that satisfy human wants. Though the framework primarily focuses on market processes, and therefore can include disordered wants, it does not preclude prescribing a moral element, and Catholic teaching can provide that.

Catholic teaching tells us that “true human wants” extend beyond the material and include goods that fulfill spiritual and social wants. Therefore, true economic progress includes a church with open doors and scheduled services, a quiet garden with seating for contemplation and reflection, and a local theater or art studio offering workshops and exhibitions, goods and services that today’s economic metrics often fail to fully capture.

So, God-focused economic progress is important, so therefore, saving, the initial step that leads to investment in productive property and permits the process, is important.

We can save in consumption goods, like 100 cans of soup. We can save in tractors or laptops. We can also save in money, which is the simplest way to save for the wage earner. A succinct quote from our friend Dr. Hülsmann, to summarize this important teaching.

“The store-of-value function of money is of vital importance, especially in an advanced economy. Saving and investment are the ultimate sources of economic progress, and both activities depend on the existence of a reliable medium that allows the transfer of value through time.” —Jörg Guido Hülsmann

Medium of exchange

The next function of money is the one most people know about, from last video: money as a medium of exchange.

Once a money has fully established itself as a store of value in a society, the price appreciation relents and its value becomes stable. People then have more freedom to use it for everyday transactions since they are not as strongly motivated to delay spending in hopes of a significant value increase.

The medium of exchange function of money was recognized by the Early Church, including St. John Chrysostom in 390 AD.

“Money was invented for the sake of exchange, that we might not be compelled to carry about all our goods, but might use a common standard to give and receive according to our needs.” —St. John Chrysostom, Homilies on Matthew, 390 AD

Unit of account

Then, finally, after the monetary good becomes widely adopted as a medium of exchange, it evolves into a unit of account.

People begin to use it as a standard measure of value for pricing goods and services. It becomes the money people think in. Here’s an exercise. How much is a hamburger worth? What does rent cost? Some amount probably comes to mind for you.

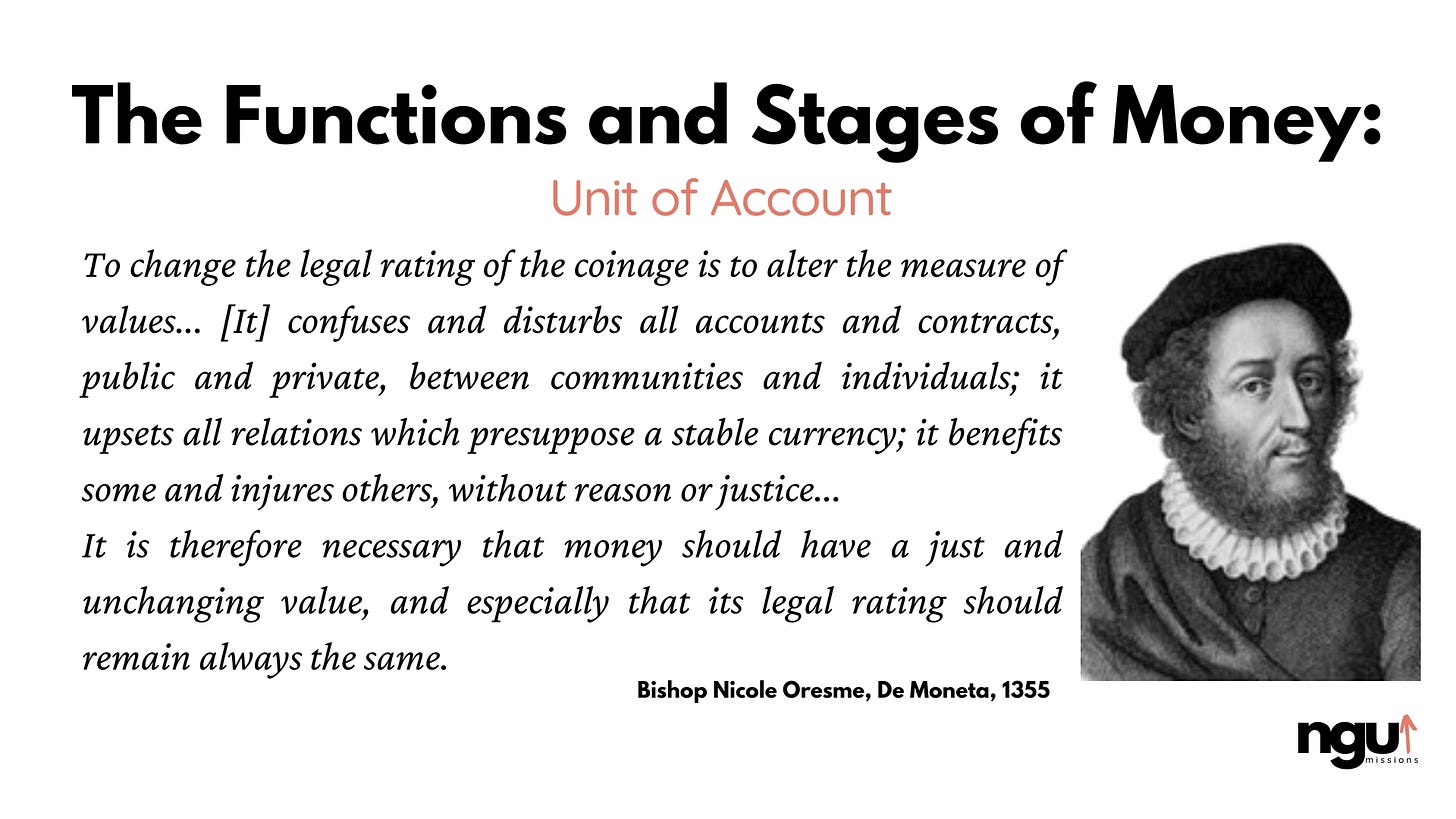

The idea of money as a unit of account has been understood for centuries. Here’s a quote from French Bishop Nicolas Oresme, often regarded as the greatest medieval economist.

“To change the legal rating of the coinage is to alter the measure of values... [It] confuses and disturbs all accounts and contracts, public and private, between communities and individuals; it upsets all relations which presuppose a stable currency; it benefits some and injures others, without reason or justice... It is therefore necessary that money should have a just and unchanging value, and especially that its legal rating should remain always the same.” —Bishop Nicole Oresme, De Moneta, 1355 AD

Recap, and where’s bitcoin?

To recap, these are the three functions and stages of money:

Store of value

Medium of exchange

Unit of account

Monetary goods that are not yet a unit of account may be thought of as being “partly monetized.” Now where are we at with bitcoin?

In 2025, bitcoin is establishing itself as a store of value.

Bitcoin is not widely used as a medium of exchange in most countries. Your local restaurant will probably say “no” if you ask them if they accept bitcoin for the payment of your bill.

And because of that, bitcoin is not a unit of account, though it is a common misconception that it is. While you can indeed buy a coffee with bitcoin in some cafes (let’s say in the United States of America), the price listed is the US dollar price sought by the merchant translated into bitcoin terms at the current USD/bitcoin exchange rate.

It will likely be several years before bitcoin transitions from being an emerging store of value to being stable and a medium of exchange and unit of account, and that path is fraught with risk and uncertainty. But the pursuit is important: the one mention of “currency” in the Catechism, in paragraph 2431 on the Seventh Commandment (Thou shalt not steal), demands a stable currency.

2431 The responsibility of the state. “Economic activity, especially the activity of a market economy, cannot be conducted in an institutional, juridical, or political vacuum. On the contrary, it presupposes sure guarantees of individual freedom and private property as well as a stable currency and efficient public services. Hence the principal task of the state is to guarantee this security, so that those who work and produce can enjoy the fruits of their labors and thus feel encouraged to work efficiently and honestly.” —Catechism of the Catholic Church

In the next video, we’ll learn seven desirable properties in money to evaluate various forms of it throughout history.

Have feedback to improve this part of the course? Submit it anonymously here.

The next part of the course will be released later this week.

Share this post